Historical Prescott Women

The women throughout the generations that have helped shape Prescott history.Sharlot Hall

Read more

Sharlot Mabridth Hall was an unusual woman for her time: a largely self-educated but highly literate child of the frontier. Born on October 27, 1870, Sharlot was given her name by an uncle who claimed it was of Indian origin. Her earliest memories were of Comanche raids, grasshopper plagues, prairie fires, and of pet buffalo killed by wolves. In 1882 the Hall family crossed the Santa Fe Trail and went on to Arizona. Her impressions of this journey remained with her all of her life. She loved ideas and the written arts and expressed her fascination with Arizona frontier life through prose and poetry. The family settled on Lynx Creek near today’s Prescott Valley. It was the final decade of the great western frontier, and its memories stayed with Sharlot.

The Hall family raised horses and mined gold on Lynx Creek, then built a homestead that they called Orchard Ranch. James and Adeline along with their children, Sharlot and Ted, kept pigs and cows and grew vegetables, apples, and pears. Sharlot’s father, James Hall, worked the hydraulic, gold mining operation on Lynx Creek. In 1890 he built a ranch above the junction of the creek with the Agua Fria River and planted fruit trees. Until 1927 “Orchard Ranch” was Sharlot’s home. However, this home was often a burden for Sharlot as she lived the title “Ranch Woman.” The hardships of ranch life, and particularly of ranch women, were a frequent theme in her writing.

Sharlot attended school for a couple of brief terms in a log-and-adobe schoolhouse four miles from the ranch, then boarded in Prescott for one year of schooling in town. There she met Henry Fleury, who had come to Prescott in 1864 as secretary to the first governor, John Goodwin, and who lived in the old log Governor’s Mansion. The gruff, grey-bearded Fleury told Sharlot many fascinating stories of Prescott’s early times.

Sharlot Hall saw the need to save Arizona’s history. The territory had been founded in 1863 and by 1900, as early settlers died, their possessions were lost, along with their stories. There was also widespread looting of Arizona’s spectacular Indian ruins to supply the eastern market with “Indian relics.” To save what she could, Sharlot began to collect both Native American and pioneer material. As early as 1907, Sharlot Hall planned to develop a museum for her collections.

In 1906, Sharlot Hall became active in the crusade against the congressional measure which would have brought New Mexico and Arizona into the Union as one state. Sharlot toured Arizona gathering opposition to the bill and wrote a 64-page article in “Out West Magazine” praising Arizona’s resources. Her epic poem, “Arizona,” describing why Arizona deserved separate statehood, was placed on the desks of each congressman. The measure was defeated, perhaps due, in part, to Sharlot’s efforts.

In an age when a woman was often considered inferior to men, she loved a good fight and broke gender barriers. Sharlot was a free soul and her writing expresses this sense of freedom.

“But I do enjoy everything – just the sunshine on the sand is beautiful enough to keep one giving thanks for eyes to see with. And all day long I’m glad, so glad, so glad that God let me be an out-door woman and love the big things. I couldn’t be a tame house cat woman and spend big sunny, glorious days giving card parties and planning dresses — though I love pretty clothes and good dinners and friends – and would love a home where only the true, kind, worth-while things had place.

“I’m not unwomanly – don’t you dare to think so – but God meant woman to joy in his great, clean, beautiful world – and I thank Him that He lets me see some of it not through a window pane.

“Your telegram came yesterday – on from Phoenix. Every one of my happiest thoughts, all the days through, ends in a prayer for you – and gratitude beyond words that I have you to call friend – dear, dear, dear Great Comrade. Goodnight, Amigo, God keep you everywhere. (signed) S. M. H.”

—Sharlot Hall to Matt Riordan, September 1910

Sharlot served as Arizona’s territorial historian from Sept. 1909 until Feb. 1912. She was the first woman to hold a salaried office in the territory. During her tenure, she visited prehistoric ruins and Indian Reservations and collected pioneer material throughout Arizona. In July 1911, Sharlot began the longest expedition of her tenure, a ten-week wagon trip across the wild, remote Arizona Strip north of the Grand Canyon.

At about this time she was also very active in the national political arena, first as a lobbyist and later as a presidential elector.

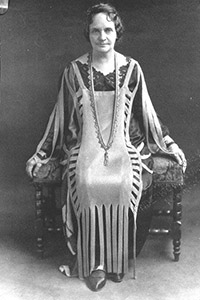

When Calvin Coolidge won the presidential election of 1925, Sharlot was selected as the elector who would deliver Arizona’s three electoral votes to Washington. For the trip the Arizona Industrial Congress commissioned an overdress of copper links which she wore to the inauguration. Later, Sharlot often wore this unusual garment with its copper accessories and a cactus hat as she lectured about Arizona and it’s resources.

Finally, on June 20th, 1927, Sharlot agreed to move her extensive collection of artifacts and documents into the Old Governor’s Mansion and open it as a museum on June 11 the following year. She signed a contract to house these artifacts in Arizona’s 1864 Governor’s Mansion and to operate it as a public museum. For the rest of her life, she worked to preserve the old log building and to save Arizona’s historic past. Sharlot had called her home and business the Old Governor’s Mansion Museum and in the 1930s with the help of the Civil Works Administration, she had the Sharlot Hall Building built behind it and began to call the new building the Sharlot Hall Museum. After Sharlot’s death in 1943, the entire museum was officially named for her.

Her diligent efforts inspired others to contribute to the preservation of early Arizona history. After her death on April 9, 1943, a historical society continued her efforts to build the complex that bears her name. In 1981 Miss Hall became one of the first women elected to the Arizona Women’s Hall of Fame.

Kate Cory

Read more

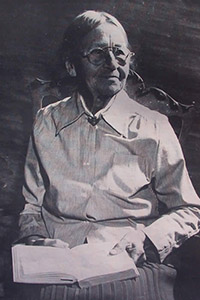

Kate Cory (February 8, 1861 – June 12, 1958) was an American photographer and artist. She studied art in New York and then worked as a commercial artist. She traveled to the southwestern United States in 1905 and lived among the Hopi for several years, recording their lives in about 600 photographs.

She moved to Prescott, Arizona in 1913 and lived in a stone house built and furnished by Hopi workers.

Because of declining attendance at the Prescott Rodeo, Cory helped a group of local men calling themselves “Smoki” (pronounced Smoke-eye) with information about Hopi ceremonies that they performed. When the Smoki grew large enough to need a permanent facility and a museum, Cory assisted with the design and decoration of the buildings. She also painted her largest paintings for display in the Smoki Museum, where they still hang.

In her earnest intention to avoid living a wasteful life, she became known in Prescott for being eccentric. Fellow church members offered to replace her torn and tattered clothes. She was frugal but gave away two cabins she owned to renters. She removed debris from rainwater and used it to develop photographs. Rather than sell her paintings, she bartered them. She was described as having had “a plain, weather-beaten face, pulled-back hair, a determined black-clothed walk with a cane as if every trip downtown were aimed at confronting the mayor.”

Her paintings are in the collections of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Sharlot Hall Museum, and the Smoki Museum of American Indian Art & Culture in Prescott. Her work is also owned by the First Congregationalist Church, where Cory was a member.

Mollie Sheppard

Read more

Mollie Sheppard, an Irish immigrant, and popular courtesan becomes rich while operating a successful brothel in Prescott, Arizona during the 1870’s. After being forced to leave Prescott through political collusion between the Ladies Morality League and the territorial governor, an array of enigmatic characters and a streak of turbulent circumstances turn Mollie’s life topsy-turvy. During the chaos that follows, Mollie almost dies when she is wounded by Indians; she fends off an assault attempt; adopts a teenager to save the girl from a life of prostitution; quits the brothel business; returns to her homeland in Ireland to join her family; and becomes a successful legitimate businesswoman. She finally finds love with a man she met aboard the ship during the trans-Atlantic crossing to Ireland.

Excerpt from “The Life of Mollie Sheppard: A Bold Independent Woman” available on Amazon here.

Big Nose Kate

Read more

Mary Katherine Horony-Cummings (born as Mária Izabella Magdolna Horony, November 9, 1849 – November 2, 1940), also known as Big Nose Kate, was a Hungarian-born prostitute and longtime companion and common-law wife of Old West gunfighter Doc Holliday.

In 1876, Kate moved to Fort Griffin, Texas, wherein 1877 she met Doc Holliday. Doc said at one point that he considered Kate his intellectual equal. The couple went with Earp to Dodge City and registered as Mr. and Mrs. J.H. Holliday at Deacon Cox’s boarding house. Doc opened a dental practice by day but spent most of his time gambling and drinking. The two fought regularly and sometimes violently, but made up after fights despite the volatile relationship.

According to Kate, the couple later married in Valdosta, Georgia. They traveled to Trinidad, Colorado, and then to Las Vegas, New Mexico, where they lived for about two years. Holliday worked as a dentist by day and ran a saloon on Center Street by night. Kate also occasionally worked at a dance hall in Santa Fe.

By her own account, Doc and Kate met up again with Wyatt Earp and his brothers on their way to the Arizona Territory. Virgil Earp had already been in Prescott and persuaded his brothers to move to Tombstone. Holliday was making money at the gambling tables in Prescott, while Kate worked as a prostitute in the upstairs rooms at The Palace Saloon; he and Kate parted ways when Kate left for Globe, Arizona, but she rejoined Holliday soon after he arrived in Tombstone

Kate died on November 2, 1940, seven days before her 91st birthday, of acute myocardial insufficiency, a condition she started showing symptoms of the day before her death. Her death certificate states that she also suffered from coronary artery disease and advanced arteriosclerosis. Kate’s death certificate contained significant discrepancies regarding her parents’ names and her birthplace. Although she was born in Hungary, her death certificate states she was born in Davenport, Iowa, to father Marchal H. Michael and mother Catherine Baldwin. The birthplace of both her parents is shown on the certificate as “unknown”. The superintendent of the Pioneer Home is named as the informant on the death certificate.

Kate was buried on November 6, 1940, under the name “Mary Katherine Horony Cummings” in the Arizona Pioneer Home Cemetery in Prescott, Arizona.

Frances Munds

Read more

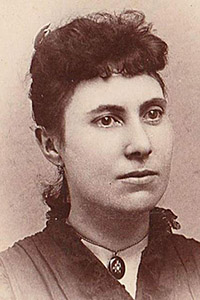

Frances Lillian Willard “Fannie” Munds (June 10, 1866 – December 16, 1948) was an American suffragist and leader of the suffrage movement within Arizona. After achieving her goal of statewide women’s suffrage, she went on to become a member of the Arizona Senate more than five years before the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution granted the vote to all American women.

After graduation, Willard joined her family in the Arizona Territory, where her four brothers operated a ranch in the Verde Valley with her father’s former business partner, William Munds (Joel Willard had died in 1879). She worked as a school teacher in the communities of Pine, Payson, and Mayer before marrying John Lee Munds, youngest son of Willard Munds, in 1890. The couple moved to Prescott in 1893 where John Munds was elected Yavapai County sheriff for two terms beginning in 1899. The couple had one son and two daughters.

In 1898, Munds was elected secretary for the Territory of Arizona Women Suffrage Organization. Together with organization president Pauline O’Neill, she reached out to Mormon women within the territory. This marked a change from the practices of earlier suffrage leaders, such as Josephine Brawley Hughes, who had shunned the Mormon community. This outreach enabled the organization to lobby Mormon members of the territorial legislature to support legislation supporting women. Munds also attended legislative sessions personally to lobby for women’s issues. After several years’ effort, the 1903 territorial legislature passed a bill granting women the vote. This legislation was later vetoed by Territorial Governor Alexander Brodie. A similar bill would later be vetoed by Governor Kibbey.

In 1909, with statehood appearing imminent, Munds struck a deal with the Western Federation of Miners in which the labor union would support women’s suffrage in exchange for the women’s organization’s support in labor issues. The next year, during Arizona’s constitutional convention, a proposal granting women’s suffrage was introduced. The proposed plank was defeated before it could be added to the constitution.

Following Arizona’s admission to the Union on February 14, 1912, a meeting of the State of Arizona Women Suffrage Organization unanimously elected Munds the organization’s president. She initially refused to accept the position, but acquiesced on the condition the position be renamed chairman, and that she be allowed to reorganize the state organization. During the summer of 1912, Munds helped organize a petition drive to collect the 3,342 signatures needed for a ballot initiative. After gathering the needed signatures, Munds then proceeded to get the support of 95% of the state’s labor unions. When the Progressive party came out in favor of the suffrage issue, Munds was able to force the Democratic and Republican parties to reevaluate their positions by threatening to throw support from women to the third party. When the election results were counted, the suffrage initiative had passed by a three-to-one margin in every county.

In 1913, Governor George Hunt appointed Munds to represent Arizona at the International Woman Suffrage Alliance in Budapest, Hungary. The next year, she, along with Rachel Berry of Apache County, became the first woman elected to the Arizona Legislature (representing Yavapai County).

Upon her entry to the state legislature in 1915, Munds said, “true blue conservatives will be shocked to think of a grandmother sitting in the State Senate.” During her time in office, she chaired the Committee on Education and Public Institutions, and also served on the Land Committee. Sen. Munds also introduced legislation doubling the widow’s tax exemption. She chose not to run for a second term in the legislature, but in 1918 was persuaded to run for Secretary of State, a run that was unsuccessful.

After leaving office, Munds remained active in politics for the rest of her life. She died at home on December 16, 1948, and was buried at the Mountain View Cemetery in Prescott, Arizona. In 1982, she was inducted into the Arizona Women’s Hall of Fame.

Viola Jimulla

Read more

Viola Jimulla (1878 – December 7, 1966) was the Chief of the Prescott Yavapai tribe. She became Chief when her husband, who was also a Chief of the tribe, died in an accident in 1940. She remained Chief until her death. She was known for improving living conditions, and for her work with the Presbyterian Church.

For twenty-six years, until her death on December 7, 1966, Viola guided her tribe with wisdom and kindness. Her leadership helped the Yavapais achieve better living conditions and more modern facilities than most other tribes.

Jimulla’s personal strengths and skills helped her people adapt and grow with the surrounding Anglo community. Although Jimulla formed a bridge between the two cultures, Anglo and Indian, she still honored the traditions of her tribe. Not only was Jimulla a great leader for her tribe, but she was also influential in religious matters. She was the first Yavapai to be baptized into the Presbyterian Church. In 1922, she and others of her tribe revitalized the Yavapai Indian Mission to become the Presbyterian Mission. Jimulla served the mission as an elder, a Sunday School superintendent, and an interpreter. In 1950, she became a commissioner to the General Assembly of the United Presbyterian Church in Cincinnati where she made a speech on behalf of the mission. In 1951, the mission became an organized church and later, in 1957, it was reorganized as the Trinity Presbyterian Church which recognized the three founding entities – the new Presbyterians in Prescott, the founding church, and the Presbyterian Indian people.[5]

Under Jimulla’s leadership, The Prescott Yavapai Tribal Council was formed to better ensure the people’s voice in their own governing. Jimulla’s descendants continued to guide her people. Two of her daughters, Grace Mitchell and Lucy Miller, became chieftess in the years following their mother’s death. In 1986, Viola was elected to the Arizona Women’s Hall of Fame. A statue of Viola teaching basketry to a young Yavapai is in the lobby of the Prescott Resort and Conference Center. The young girl in the statue is her granddaughter Patricia McGee, who, in 1972, became tribal president.

Grace M. Sparkes

Read more

Grace Sparkes was born in Lead, SD, on January 21, 1893. She came with her family to Prescott in 1907 and graduated from St. Joseph’s Academy in 1910. Later she received a degree from Lamson Business College in Phoenix.

Grace served as secretary of the Prescott / Yavapai Chamber of Commerce, from 1911 until 1945. She helped organize the Prescott Frontier Days for 30 years. She was known throughout the West as “the girl who bosses 200 bronco busters.” Sparkes helped establish general rodeo rules, many of which are still used by professionals today. She is also credited with coining Prescott’s slogan: “Cowboy Capital of the World.”

Seeing the need for a first-class hotel downtown, Grace spearheaded funding and construction of the Hassayampa Hotel. In 1921, she helped organize the Smoki (pronounced smoke-eye) People of Prescott which promoted Indian lore for over 70 years.

As chairman of the Yavapai Civil Works Administration in 1933-34, Sparkes was instrumental in securing the New Deal funding necessary to construct many buildings and improvements that are still with us today. These include the Lindley Field and Park; the Smoki Museum; and no less than four road bridges in Prescott.

In 1935, Grace and Sharlot Hall, with Yavapai leaders, Sam and Viola Jimulla, secured 75 acres of land to create the Prescott Yavapai Indian Reservation. Sparkes also secured money for the Yavapai Indians to build their own houses on the new reservation.

Sparkes played a crucial role in preserving other historic sites in Arizona including the Coronado National Memorial, the Tuzigoot Indian Ruins, and the Montezuma Castle National Monument.

Sparkes spearheaded the effort to bring us Interstate 10–a faster way to California and an economic boom for the state.

Upon her retirement in 1945, she moved to Cochise County to oversee her own mining claims. She also enjoyed hiking, horseback riding, and reading.

The Old Armory building in Prescott is now named The Grace M. Sparkes Activity Center in her honor, as well as the bridge on Williamson Valley Rd. that crosses over Mint Wash.

Grace Sparkes passed away at age 70 on October 22, 1963, and was buried in the family plot at Mountain View Cemetery, Prescott.

Because of her effective interest in public welfare and her estimable personal qualities, she had an extensive number of acquaintances and was highly esteemed by all who knew her.

She was inducted into the Arizona Women’s Hall of Fame in 1985.

Elisabeth Ruffner

Read more

On September 17, 1919, in the Mt. Airy neighborhood of Cincinnati, Ohio, Elisabeth Alma Friedrich (Ruffner) came into the arms of her parents, Clara and William. World War I was over, and the country was eager for peace and security. Between the flu pandemic, race riots, the anti-communist blacklist, and domestic terrorist bombings, domestic peace was elusive. A Constitutional amendment gave women the right to vote, and prohibition became the law of the land.

The youngest of three, Elisabeth attended Indiana University and the University of Cincinnati, working toward a medical degree. Her career plans were interrupted by a handsome young man she met on a blind double-date, he with her sorority sister.

This dashing fellow, “Budge,” was enrolled in the mortuary college, and he and Elisabeth dated through the spring of 1940. After Budge returned to Prescott, Arizona, plans were made for Elisabeth and her mother Clara to stop at nearby Ash Fork on their way to Los Angeles on business. Lester Ward “Budge” Ruffner proposed before the week was out, and Elisabeth and he were married on August 10, 1940, at the Ruffner home on Park Avenue in Prescott.

With the onset of World War II and Budge in the Army Air Corps for three years, Elisabeth found herself a war bride with a new baby by 1941. She took a job with Dr. Florence Yount, setting up a new laboratory and filling in for the doctor as she traveled the county making house calls. Elisabeth adored the opportunity to work in medical practice in Prescott, partially fulfilling her career ambitions.

At the end of the war, Elisabeth turned her attention to family life with daughter Melissa, who was then 4, as well as volunteering with the Girl Scouts, and the public library board. Daughter Rebecca was born in 1947, and son George in 1950. For many years, Budge and Elisabeth worked side by side in the family business, Ruffner Funeral Home, which had come into the family in a storied 1903 Whisky Row poker game.

Among Elisabeth’s proudest accomplishments beyond her family life was her work in establishing the Yavapai Community Hospital and auxiliary, PEO Chapter Y, the Prescott Arts and Humanities Council, Friends of Arizona Highways, the Rails to Trails program, the Open Space Alliance, and the Friends of the Prescott Public Library. Bitten early by a deep love of Western historic architecture, Elisabeth incorporated the Yavapai Heritage Foundation, through which funds were quickly raised to move the Bashford House to the Sharlot Hall Museum grounds. That sparked her interest in a growing national movement, which led to her serving as an advisor with the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Some 1,200 buildings in Arizona are now on the National Register because of her tireless advocacy to protect and preserve the community legacy they represent. Prescott residents and visitors today enjoy many local landmarks that distinguish the downtown area, including the Carnegie Library, Octagon House, Hotel Vendome, Hassayampa Inn, Elks Opera House, and the Yavapai County Courthouse Centennial Cornerstone, largely because of Elisabeth’s ability to bring resources together to help property owners achieve their preservation goals.

Elisabeth was recently inducted into the Arizona Women’s Hall of Fame, one of the first living women so honored. On March 13, 2019, surrounded by the love of her family, dearest friends and in the tender care of Marley House staff, Elisabeth slipped away.

For more info about Elisabeth Ruffner and her love of volunteering, read the story here.

Mollie Monroe

Read more

Mary E. Sawyer (1846-1902), better known as Mollie Monroe, was an American old west woman who was known for cross-dressing and for her liaisons with multiple men, among other things.

Monroe fell in love with a man as a teenager. Both her family and her boyfriend’s family agreed that the couple was too young to marry, and the man was sent away.

Monroe then decided to go after her boyfriend, disguised as a man and calling herself Sam Brewer. Her search ended in sadness when she discovered her boyfriend had been murdered by a gang during a bar brawl.

Monroe then swore to avenge his death, crossing virtually every city from Utah to northern Mexico. She failed to find her boyfriend’s killers and became an alcoholic.

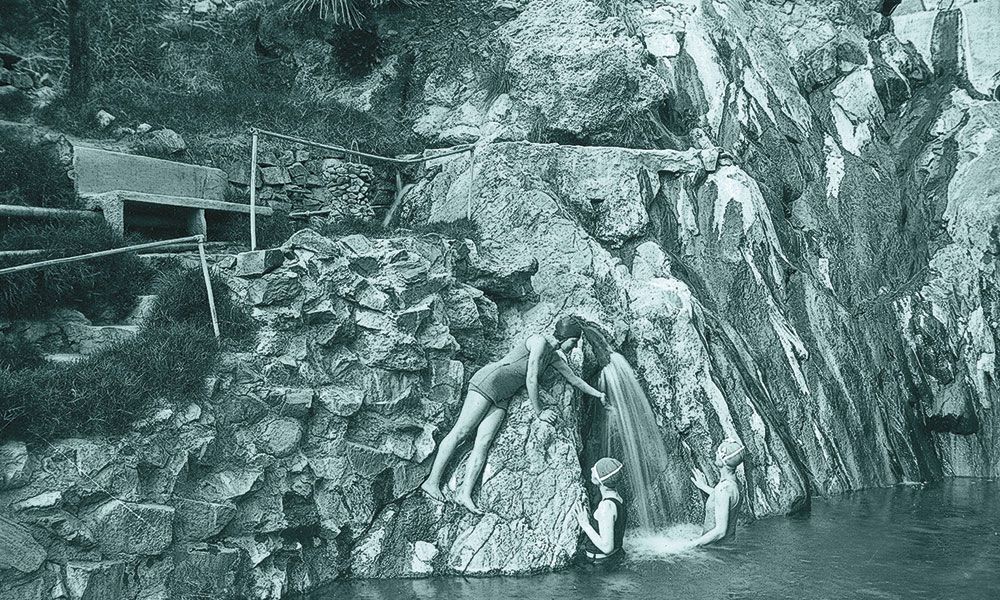

Around 1870, she met George Monroe, a well known and rich miner. Mollie and George Monroe married and settled in Wickenburg, Arizona, where they mined together. In 1874, they moved to Prescott, Arizona. George Monroe had discovered a water spring there. He turned it into a resort and named it “Monroe Springs”. The attraction drove many tourists from around the country.

Mollie Monroe was also a gambler. Apart from her alcoholism, her gambling addiction also led her to lose a considerable amount of money, once selling a gold mine she had discovered for around $2,500 dollars, then gambling the money away in about a week.

Despite her addictions, Monroe enjoyed helping needy people, such as prostitutes, lone women, and their children. Legend has it that once she met a woman and her children; having been told by the woman that her husband went to town for supplies three days before and had not returned, she went searching for the man, and found him in a bar. She then led him out of the bar, tied him to her horse, and dragged him all the way back to his house, staying overnight to make sure he wouldn’t leave the house again.

A newspaper report also told of her saving the lives of 20 army men when attacked by Apaches. According to the article, she had left the men to look for items to cook with, and when she returned, she noticed that the army men were surrounded by Apache and that two army men had already been killed. She and her friend, Texas Johnson, fired shots into the air, and the Apaches ran, according to the news.

Mollie Monroe was despised by most of Prescott’s high society women, for what they viewed as “manly manners” and, as a popular publication of the time said, “morals that are dissolute”.

In 1877, she was found wandering across the streets of Peeples Valley by a policeman named Ed Bowers. Brought to trial, she was found to be insane on May 9 and sent to a sanitarium in Stockton, California.

Along the way to Stockton, she and Bowers were attacked by thieves. Other than Bowers losing a watch and some 450 dollars, the lawman and Monroe came out unscathed from the attack.

Mollie Monroe’s times at the California asylum did not go without controversy: she tried burning the building once, causing her to be sent to San Quentin jail. Once there, she forged a friendship with former Arizona governor A.P.K. Safford (after whom the city of Safford, Arizona is named). Many viewed this as an attempt by Mollie to get out of San Quentin.

In 1887, she was sent to a new asylum built in Phoenix. In 1895, she escaped the asylum and was found four days later. With only a few crackers and a bottle of water taken to support herself, she was found bleeding and in bad overall health.

Her health, troubled by her alcohol problems, continued to decline, and in 1902, she died in the Phoenix asylum.

Margaret (Williams) Ehle